When does a chair cease existing as a chair and become something else, like a makeshift shelf or simply clutter on the roadside? Such a question pervades the work of Maxwell Ijams, an American expat from Salt Lake City, Utah, and photographer currently living and working in South Korea.

Ijams specializes in found art photography and has published two photo books documenting the subject. Ijams is also a musician specializing in drone and ambient music, which at times plays into his photographic philosophy.

I recently got the chance to speak with Ijams to find out more about his music and photos, reasons for living in Korea, and what’s next in his artistic journey.

What brought you from Salt Lake City to Asia and Korea?

I originally studied abroad in Asan, South Korea, during my undergraduate studies and fell in love with Korea. I moved there as a teacher after earning my BA, and while I had a limited understanding of what it meant to be a good teacher in my initial years yet found immense joy in working with and learning alongside children. Understanding the limited scope of what the Korean private education system could offer, I decided to work on becoming a more effective teacher.

I received my Master’s in Applied Linguistics in 2023 to better prepare my students with critical thinking skills, which I think education around the globe lacks. I am not sure if this is the country where I will be forever, but in the meantime, I enjoy Korea for its brash honesty and unrelenting energy. The shrinking streets of downtown Seoul offer so much in terms of found sculpture, which I am drawn to as a photographer.

How has your choice of home influenced your work?

I am an introverted person, so I spend most weekends alone. Photography is a good chance for me to get out of the house and explore new neighborhoods. Also, Seoul’s rapid expansion and ever-changing city life have created an overlapping rhythm of objects that is a highly addictive, artistic pursuit. There are so many examples of objects being used for their unintended purpose. I have thought about exploring all these other objects, but I feel like I don’t have the skill to capture their expressions. I hope I can expand my eye to give them light.

How did you get started with photography, and what led you to photograph chairs and stools as a subject?

When I was younger, I would build cameras. I’d use homemade pinhole cameras to experiment with different internal mechanisms like mirrors, different apertures, and body materials. I never focused on form, just the process of leading light to film. Then I put photography aside as a hobby to focus on music, and it wasn’t until I moved to Korea that I started shooting again.

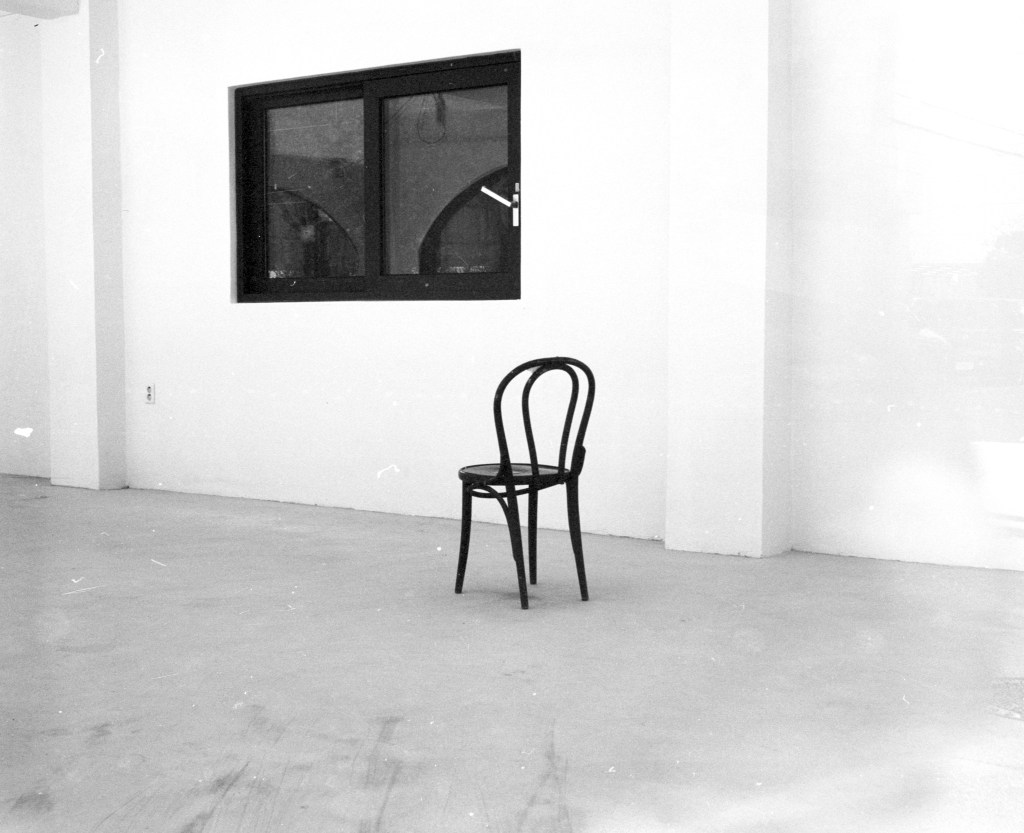

In terms of my subjects, I have three main reasons for focusing on chairs. First, Genpei Akasegawa and the Hyperart Thomasson movement of found art were both major inspirations for me. Second, I question an object’s linguistic self: When does a form no longer exist as itself? Finally, my obsession with chairs is a love letter to Korea. I aim to show the heuristic pulse of Korean culture.

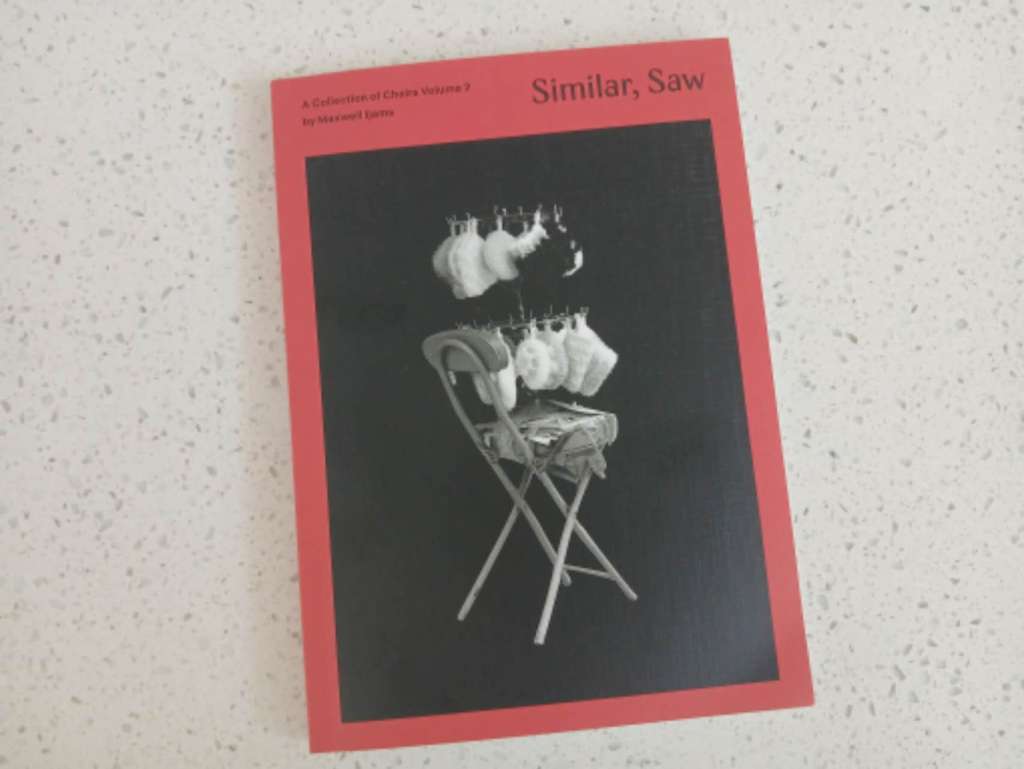

In your most recent photo book, Similar, Saw, you begin by stating you view your subjects – chairs, stools – through a lens of what it means to be, writing “My subjects are broken or offer no respite, yet they are still themselves, through our words.” How did you reach this realization?

The myriad of unusable chairs is astounding. I am drawn to looking at all objects in this sense. As I mentioned above, where do we draw the line when an object no longer becomes itself? I love discussing this very topic with my students. Children have such a keen, curious understanding of the world. They love looking at each of my photographs and telling the story behind them. I am unable to see how the chairs I find wind up where they do, so I love to hear my students narrate their lives.

Along with photography, you also make music, specifically drone music. What drew you to this genre?

My obsession with drones and classical music started at an early age. I would often sit at my electronic piano and play one organ chord for minutes at a time, only changing a note here and there. I never realized I was playing ambient music until I started to listen to Brian Eno and William Basinski. My taste for ambient music grew stronger when I met my good friend Isaac, and we would play around with sounds in his studio in Portland. We later went on to record under the name Anxiété Sublimant. I adore the space that is present in ambient music; there is so much stillness in the sound. I find that ambient music helps calm my mind, like a cool compress to the brain.

Is there any overlap or correlation between your photographs and music?

My earlier photography was very static. I shot mainly high ISO black and white films. Furthermore, in my darkroom, I would add more developer, use warm water (which is generally only used for color development), or develop for longer than the recommended time. I love the binary on and off that grainy, overdeveloped black and white film brings. My favorite author, W.G. Sebald, writes about the shadows of reality that appear in film photography, of which he also shot black and white.

Moreover, much of my early ambient music was staticky and still, like my photography. Now, though, I shoot lower ISO films and prefer less noisy pictures and sounds. Regarding my music, I am working on a slower, more melodic ambient record, which should be released later this year.

What other projects are you working on, if any?

To further remark on Hyperart Thomassons, I have noticed the remnants of removed objects and have begun to photograph them. For example, a missing window that has been cemented over, or a staircase that leads into a wall. These have been my main drives to pick up my camera and walk. I have one last chair-related project: I want to work on portraiture by taking photos of people and their chairs. These could be chairs that they use at work or to create art. I want to have a side-by-side of a person and their chair. I want to explore the connection between people and the objects they use in their daily lives.

You can find more of Ijams’ on his website, which has links to his photo books and music.

Leave a comment